Protein-Rich Foods and Their Role in Human Energy and Macronutrient Balance

An educational exploration of protein as a macronutrient, food sources, and energy contribution.

Protein as a Macronutrient: Fundamentals

Protein stands as one of three primary macronutrients essential for human physiology, alongside carbohydrates and fats. As an organic compound composed of amino acids, protein provides 4 kilocalories per gram, identical to carbohydrate energy density but distinct from fat at 9 kilocalories per gram.

Unlike carbohydrates and fats, protein serves dual roles: it functions both as an energy source and as a structural and functional component of body tissues. The body requires amino acids for synthesis of enzymes, hormones, antibodies, and structural proteins in muscle, bone, and connective tissue.

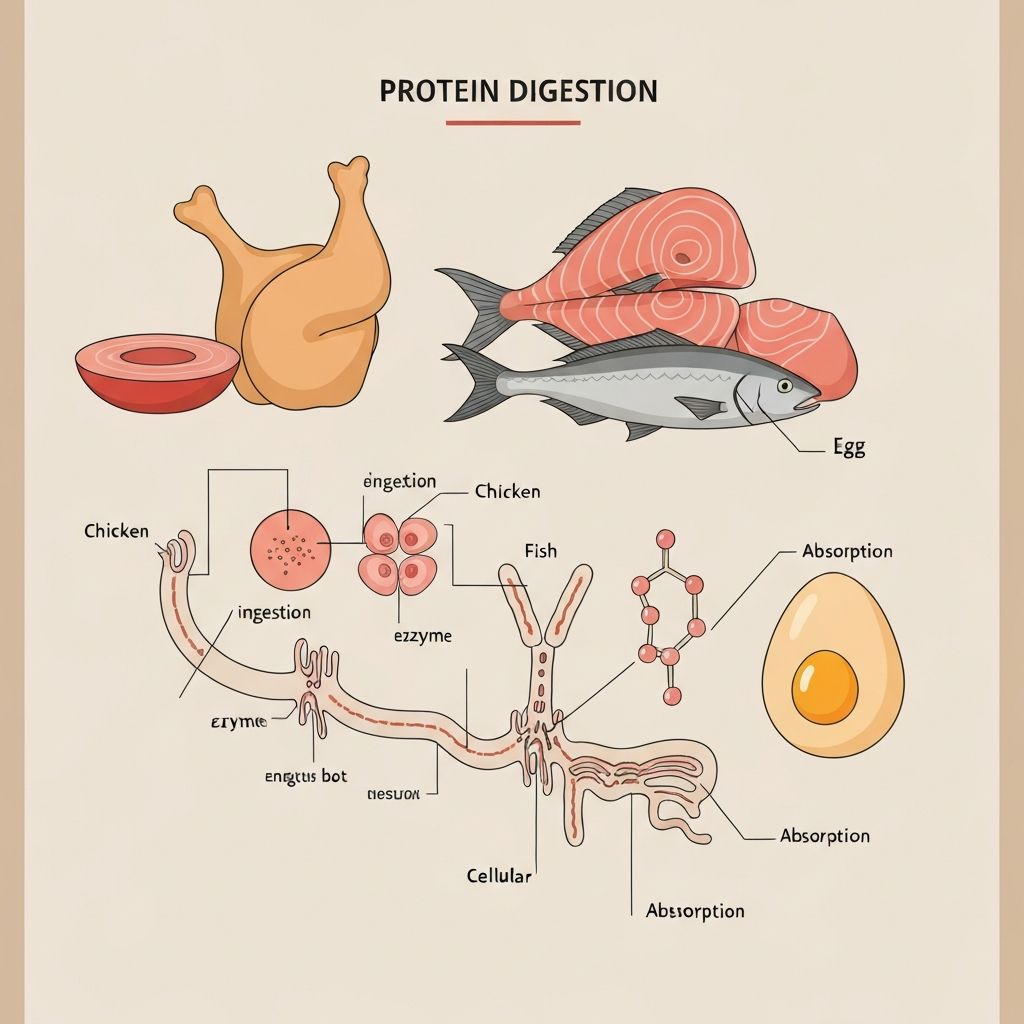

The process of protein digestion begins in the stomach, where hydrochloric acid and the enzyme pepsin initiate breakdown. This process continues in the small intestine through pancreatic proteases and intestinal peptidases, ultimately releasing individual amino acids for absorption.

Protein Quality Metrics Explained

Protein quality assessment relies on specific metrics that evaluate the amino acid composition and digestibility of protein sources. Two primary measures in contemporary nutritional science are PDCAAS and DIAAS.

PDCAAS (Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score)

Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score evaluates both amino acid profile and digestibility. The metric examines whether a protein source contains all nine essential amino acids in adequate ratios. A score of 1.0 represents complete protein quality, indicating the food supplies amino acids in proportions that meet human requirements.

DIAAS (Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score)

The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score represents a refinement of PDCAAS methodology, employing more precise measurement of amino acid digestibility in humans. This metric gained prominence through WHO and FAO recommendations as a more accurate assessment method. DIAAS accounts for individual amino acid absorption at the terminal ileum, providing location-specific digestibility data.

Amino Acid Profiles

Complete proteins contain all nine essential amino acids: histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine. Animal-derived proteins typically demonstrate complete profiles, while plant-based sources may lack or contain limited quantities of specific amino acids. However, consumption of varied plant proteins throughout the day provides complete amino acid coverage without combining specific foods at single meals.

Animal-Derived Protein Sources

| Food Source | Protein (g/100g) | Quality Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Chicken Breast (cooked) | 31 | Complete, high DIAAS |

| Beef Lean Cut (cooked) | 26 | Complete, high DIAAS |

| Salmon (cooked) | 25 | Complete, high DIAAS |

| Tuna (canned in water) | 24 | Complete, high DIAAS |

| Turkey Breast (cooked) | 29 | Complete, high DIAAS |

| Pork Tenderloin (cooked) | 27 | Complete, high DIAAS |

| Whole Egg | 13 | Complete, reference standard |

Plant-Based Protein Sources

| Food Source | Protein (g/100g) | Amino Acid Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Lentils (cooked) | 9 | Complete when combined |

| Chickpeas (cooked) | 8 | Complete when combined |

| Black Beans (cooked) | 8 | Complete when combined |

| Tofu (raw) | 15 | Complete |

| Tempeh (raw) | 19 | Complete |

| Hemp Seeds | 10 | Complete |

| Pumpkin Seeds | 9 | Incomplete, lower lysine |

| Quinoa (cooked) | 4 | Complete |

Dairy and Egg Protein Characteristics

Dairy products and eggs represent prominent animal-derived protein sources with distinctive characteristics relevant to nutritional composition and bioavailability.

Dairy Protein Components

Milk contains two primary protein types: casein and whey. Casein comprises approximately 80% of milk protein and forms a curd precipitate in acidic conditions. Whey represents the remaining 20% and remains soluble across broader pH ranges. Both protein types contain complete amino acid profiles. Greek yogurt demonstrates elevated protein density through concentration of milk solids, typically providing 10-17g protein per 100g depending on fat content. Cheese protein density varies significantly based on moisture content and processing methods, ranging from 7g in soft cheeses to 36g in hard varieties per 100g.

Egg Protein Characteristics

Eggs serve as the reference standard for protein quality in nutritional assessment, traditionally assigned a PDCAAS score of 1.0. An entire medium egg contains approximately 6 grams of protein distributed between yolk and white. Egg white specifically comprises 90% water and 10% protein, with minimal fat. Egg yolk contains lipids and fat-soluble vitamins alongside protein. The biological value of egg protein—measuring amino acid retention after absorption—reaches approximately 97%, representing exceptional efficiency in human nutrition.

Protein Digestibility and Absorption

The physiological process of protein digestion and absorption encompasses several distinct phases. Following ingestion, the stomach secretes gastric juices containing hydrochloric acid and pepsin, initiating protein breakdown into smaller polypeptides and free amino acids. This phase typically lasts 1-3 hours depending on meal composition and gastric factors.

The mixture proceeds to the small intestine, where pancreatic proteases (trypsin and chymotrypsin) continue breakdown, alongside intestinal brush border peptidases completing the process to individual amino acids. The small intestine achieves absorption through specific transport mechanisms, moving amino acids across the intestinal epithelium into blood circulation. Different amino acids employ distinct transport systems, explaining why amino acid absorption timing varies.

Absorbed amino acids travel via portal blood directly to the liver, which distributes them systemically for utilization in protein synthesis or metabolism. Absorption efficiency varies based on protein source, food preparation methods, and presence of other nutrients. Cooking protein generally increases digestibility through structural changes that enhance enzyme access.

Thermic Effect of Protein Compared to Other Macronutrients

The Thermic Effect of Food (TEF), also termed postprandial thermogenesis, represents the energy expenditure associated with digestion, absorption, and nutrient processing. TEF accounts for approximately 10% of daily energy expenditure in individuals consuming mixed diets. The magnitude of TEF varies significantly across macronutrients based on digestive efficiency and metabolic processing requirements.

Comparative TEF Values

- Protein: 20-30% of consumed energy (highest TEF)

- Carbohydrates: 5-10% of consumed energy

- Fats: 0-3% of consumed energy (lowest TEF)

Protein demonstrates the highest TEF among macronutrients due to multiple factors: synthesis of transport proteins, amino acid metabolism and transamination reactions, and maintenance of protein integrity. These processes demand ATP (cellular energy), thereby elevating metabolic rate during protein digestion. Scientific literature documents this phenomenon as a consistent finding independent of protein source—animal or plant-derived proteins both demonstrate comparable TEF.

However, the practical significance of TEF in daily energy balance remains modest. A 2000 kilocalorie diet with 25% protein content (125 grams) generates approximately 25-75 kilocalories of TEF expenditure—meaningful but not substantial relative to total daily expenditure. This distinction separates the biochemical reality of elevated TEF from misconceptions regarding protein consumption as a primary weight management tool.

Protein in Mixed Meals Context

Protein consumed within mixed meals—combined with carbohydrates, fats, and other nutrients—demonstrates altered digestion and absorption characteristics compared to protein consumed in isolation.

Dietary fat slows gastric emptying, prolonging the presence of food in the stomach and extending the digestion timeline. Carbohydrates influence insulin secretion, affecting metabolic partitioning of amino acids toward anabolic (tissue-building) processes. Fiber content in whole grains and plant sources can chelate minerals and slightly reduce protein bioavailability, though this effect remains minor in typical mixed meals.

Meal composition throughout the day establishes total nutrient intake patterns more significantly than individual meal timing or macronutrient ratios at specific meals. Distributed protein intake across multiple meals supports consistent amino acid availability throughout waking hours, supporting steady protein synthesis processes. This pattern contrasts with highly concentrated protein consumption at single meals, which can overwhelm absorption capacity, with excess amino acids undergoing oxidation rather than incorporation into body proteins.

The synergistic effects of complete meals—protein with vegetables providing phytonutrients, whole grains providing fiber and micronutrients, and healthy fats supporting fat-soluble vitamin absorption—reflect the practical nutritional context where isolated macronutrient analysis provides incomplete understanding of food value.

Links to Detailed Protein Food Articles

Explore comprehensive analyses of specific protein-containing food categories and their nutritional characteristics through our detailed articles:

Protein in Poultry and Meat: Data Overview

Comparative protein content and amino acid profiles across chicken, turkey, beef, and other meat categories with DIAAS scores.

Read Article

Fish and Seafood as Protein Sources: Nutritional Profiles

Nutritional composition of salmon, white fish, shellfish, and other marine protein sources with omega fatty acid data.

Read Article

Legumes and Pulses: Plant Protein Characteristics

Protein density and amino acid profiles of lentils, chickpeas, beans, and other pulse crops with bioavailability data.

Read Article

Eggs and Dairy: Complete Protein Foods Explained

Protein quality metrics of eggs, milk, yogurt, and cheese with detailed amino acid composition analysis.

Read Article

Nuts, Seeds and Grains: Protein Density and Quality

Protein content and amino acid profiles of almonds, seeds, quinoa, and other plant-based concentrated protein sources.

Read Article

Protein Bioavailability Across Food Groups

Research-based analysis of how digestibility and absorption efficiency vary across animal and plant protein sources.

Read ArticleCommon Data Misinterpretations

- "Protein creates muscle." Protein provides amino acids for muscle tissue synthesis, but muscle development requires mechanical stimulus (resistance exercise) combined with adequate protein, energy, and recovery.

- "All protein sources are identical." Amino acid profiles and digestibility vary significantly between animal and plant sources, influencing bioavailability and physiological effects.

- "Protein timing matters more than total intake." Distributed protein across the day supports consistent amino acid availability, but total daily intake demonstrates greater influence on protein balance than specific meal timing.

- "Plant proteins lack amino acids." Plant proteins contain all amino acids; varied consumption throughout the day ensures complete amino acid coverage without requiring specific meal combinations.

- "Higher protein consumption increases metabolic rate substantially." While protein demonstrates elevated TEF, the magnitude remains modest relative to total daily expenditure.

- "Protein beyond individual requirements is stored as fat." Excess amino acids undergo oxidation for energy or transamination to other compounds; protein does not directly convert to adipose tissue.

- "Cooking protein destroys its nutritional value." Cooking generally improves protein digestibility through structural denaturation facilitating enzyme access; nutrient retention depends on specific cooking methods.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much protein do humans require daily?

Protein requirements vary based on body composition, activity level, and health status. General population recommendations range from 0.8 to 1.0 grams per kilogram of body weight for sedentary adults. Athletes, older adults, and individuals in recovery may require 1.2 to 2.0 grams per kilogram. Individual circumstances vary substantially; consult healthcare providers for personalized assessment.

Can vegetarians and vegans obtain adequate protein?

Yes, plant-based diets can provide adequate protein through varied legumes, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and fermented soy products. Total daily protein intake matters more than individual meal composition. Varied plant protein sources consumed throughout the day supply complete amino acid profiles.

What is "complete protein"?

Complete proteins contain all nine essential amino acids in proportions meeting human requirements. Animal-derived proteins typically demonstrate complete profiles. Plant sources vary; legumes often require dietary variety for complete daily amino acid intake.

Does protein timing influence muscle protein synthesis?

Research indicates that total daily protein intake influences protein balance more substantially than specific timing of consumption relative to exercise. Distributed protein intake throughout the day supports consistent amino acid availability for ongoing protein synthesis.

Are amino acid supplements necessary?

Whole food protein sources provide amino acids alongside additional nutrients including vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients. Food-derived amino acids demonstrate superior bioavailability compared to isolated supplements in most populations without specific medical conditions.

How does protein interact with kidney function?

Adequate protein intake maintains normal kidney function in healthy individuals. However, individuals with compromised kidney function require medical supervision regarding protein intake. This distinction separates normal physiological protein metabolism from pathological responses requiring clinical management.

Explore Macronutrient Science Deeper

This resource presents evidence-based information about protein as a macronutrient and its role in human energy and nutrient balance. Understanding the biochemistry and physiology of protein digestion, absorption, and metabolism provides context for informed personal decisions regarding food choices and dietary patterns.

The study of macronutrient science continues to evolve through research examining individual responses to varied dietary compositions, biological mechanisms underlying nutrient processing, and long-term health outcomes across diverse populations. As scientific understanding advances, nutritional guidance reflects emerging evidence while maintaining recognition of individual variation in physiological response and preference.

Continue to Related Articles